Energy asset developers have information needs in multiple timelines. Some needs are nearly instantaneous, such as price(s) and volume(s), and are ‘structured’ in data parlance. They are numbers, in forms easily accessed via download or API, and easily integrate into other structured data or models.

[Editor’s note: Halcyon’s Gas Power Plant Tracker and Large Load Tariff Tracker can help energy professionals keep track of the planned and in-development infrastructure powering this capex boom.]

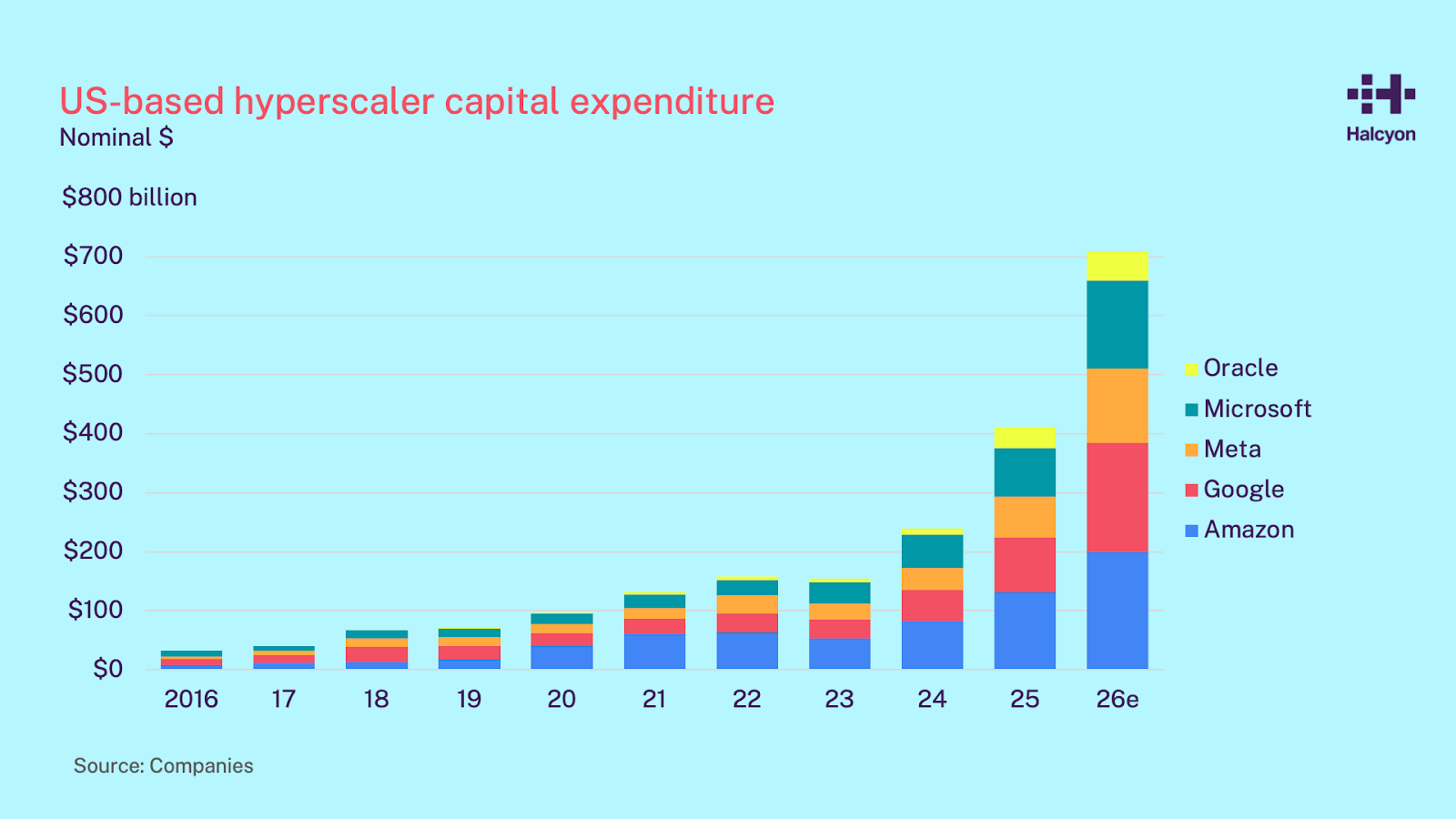

I will start this week’s writing with a fairly safe assumption: if you are reading this, you are aware that the world’s biggest technology companies are now the world’s biggest investors in physical assets and compute. Five large technology companies are on track to invest more than $700 billion in 2026, an increase of about $300 billion dollars from just last year. I am a student of capex booms, from one I watched with curiosity during my college years (broadband) to another that I scrutinized very closely as part of my work (US oil/gas exploration and production). I cannot say that hyperscaler capex has snuck up on anyone, but it still is a bit astonishing.

A few things about this figure. First, it is only the five hyperscalers. This does not include the additional investments of many other information technology companies. It does not include investment committed by the hyperscalers’ partners. Nor does it include the investment in everything that supports all of these structures and compute, such as power utility investment, fiber, water, roads, and everything else. This $700 billion+ figure is a lower bound, not an upper bound, on the AI capex boom.

It is not just a huge absolute number, but also a huge relative number too. The Wall Street Journal published a useful article this week on companies’ plans, which it contextualizes with other capex booms such as the US buildout of railroads in the 1850s, or the Apollo space program, or the U.S. interstate highway system. It includes the Louisiana Purchase as well, for good measure. I added the two booms I mentioned above (Oil/gas E&P and broadband) for more recent comparison.

-Feb-11-2026-06-18-57-7618-PM.png?width=700&height=394&name=unnamed%20(1)-Feb-11-2026-06-18-57-7618-PM.png)

So — not only is today’s hyperscaler capex huge, it is also a bigger one-year commitment of capital, as a share of national GDP, than anything in U.S. history, except the purchase of 530 million acres of land 223 years ago. I have faith in clean simple numbers, which these are; we really have not seen anything like this before.

Why We Build First

But just because something has not been seen before, does not mean we cannot think about it constructively and analogically. Think of this $700 billion not just as a capital outflow, but as an intersection of supply and demand.

Look at the chart above. I think we can classify most of these capex efforts as related to supply. The Louisiana Purchase increased the supply of land in the young United States. Railroads increased the supply of transportation; highways did the same. Hydrocarbon E&P and broadband increased the supply of energy-dense molecules and the photonic carrying capacity of telecommunications networks. Most of what we build, in other words, has been about giving us more to work with.

But we should also think of capex as demand in and of itself: demand for capital. Physical supply precedes physical demand, but financial demand comes even before physical supply. Capital enables building. The flow, then, is demand for capital -> supply of physical capability -> demand for that capability.

There is an element in each one of these booms of inducing demand as well. The Apollo program increased our supply of orbital lifting capability, and subsequently inspired demand that otherwise would not have existed for that service. Highways created demand for new ways of traveling and living; railroads enabled more demand for goods from far away and enabled new supply chains that had hitherto been rate limited by slow travel speed. In some cases, it took years for demand to materialize; for instance, much of the fiber laid in 2000 remained dark for years — but demand always rises to meet supply. No fiber stays dark forever.

How, then, do I think of the hyperscale boom? First, it is well-capitalized. Historically, hyperscalers have funded their capex needs through their own operations; today, they access pretty much every corner of the bond market. Financial markets know how to weigh the risk of borrowing to fund capital expenditure, but right now, the markets deem the risk to be worth the reward.

Second, it is ambitious. A lot more compute is being built than there is current demand for end-use consumer and business AI services. Exponential View puts the current AI market at about $14 billion a month in December 2025, and a very expansive measure puts it at possibly $4.8 trillion in 2033. I hypothesize that demand will catch up to supply, but that does not change the scope of ambition today.

Third, much of this capex is short-lived. There’s plenty of debate right now about the useful life of a GPU, but even the far end of assumptions is an order of magnitude less than the life of a railroad or a highway. We still ship goods on systems laid down in the 1850s; we might not be running processes on this decade’s Blackwells in the mid-2030s.

Looking Back to Look Forward

So, which past capex booms give us the most insight into today?

In terms of asset lifetime, hyperscaler capex is actually closest to the 21st-century boom that seems to be memory-holed: oil and gas exploration and production amid flourishing hydraulic fracturing. North America (mostly U.S.) investment in onshore E&P topped $300 billion in 2014, equivalent to 1.6% of GDP. But that investment went to short-cycle exploration, and also to short-cycle production: wells which were quick to drill, and also quick to deplete. Eventually, the market required more capital discipline, and a capital expenditure boom turned into a capital bust.

But in the process, something intriguing happened. U.S. oil production kept moving up, and in fact has never been higher, with fewer rigs, leaner teams, and optimized processes at every level. There are 80,000 fewer people working in U.S. oil and gas extraction today than there were in 2015, and about 40% more field production of crude oil in the U.S. than a decade ago. The result of a short-term upward squeeze on costs was a long-term resilience and flexibility that created an industry that is the envy of its peers elsewhere in the world.

-Feb-11-2026-06-24-04-8064-PM.png?width=1600&height=900&name=unnamed%20(2)-Feb-11-2026-06-24-04-8064-PM.png)

Or, perhaps today’s hyperscaler capex is closer to the Apollo program: a huge amount of funding devoted to the bleeding edge of new hardware and new processes, and the creation of entirely new integrated systems as a result. Those assets also depreciated quickly, but the learnings gained in the process accrued deeply and broadly across aerospace. Each new rocket design supplanted the one before it, at the same time that a long tail of capabilities extended backwards and outwards from the leading edge.

What assets do we still have from the Apollo program? Physical launch sites and all of the durable infrastructure for fueling and maintaining, launching and recovering rockets. Their optionality continues decades after the last Saturn V was launched. By analogy: today’s GPUs are the Space Race’s rockets; today’s data centers, with their multi-decade tenancies and multi-decade power and infrastructure provisions, are its Cape Canaverals.

But, there’s also a final option. It’s a looser analogy, but I still like it: perhaps AI’s investment boom today is closest to the Louisiana Purchase. An audacious, once-in-forever option that would double what was possible almost overnight. It was also something fast-moving; President Thomas Jefferson later described France’s sudden interest in selling the land as “a fugitive occurrence.” It was negotiated through an agreement that actually exceeded the authority of the parties negotiating it, the French foreign minister and the US Minister to France. And, even its most fundamental parameters were uncertain; the exact boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase were not settled with France and England until years after the Purchase closed.

It was easy, at the time, to see the strategic rationale of owning the port city of New Orleans and controlling access to the lower Mississippi. The advantages of controlling new land all the way to the Rockies was perhaps less immediately obvious, but no less powerful.

What was not possible to see, at the time, was what could be done on that land with technology and intentions which did not yet exist. The first railroad was more than 20 years away; the McCormick Reaper was another decade out. The land was lacking in technology, but new territory also inspired the inventions that would make it technology-rich.

Jefferson’s ultimate rationale for the Louisiana Purchase could be the justification of today’s foundation model builders, in early 19th century language: “it is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; & saying to him when of age, I did this for your good.” Perhaps today’s capex boom contains elements of all those which precede it, but none more so than expanding the scope of what is possible.

.png?width=50&name=34C0AE28-DE08-4066-A0A0-4EE54E5C1C9D_1_201_a%20(1).png)